It has become especially noted and critiqued at some length that I deliver a certain questionable layer of aesthetic to presented artworks and the documentation; of which takes place through photography.

It is true, when I look through the lens I do tend to look for an image, its composition, the light, and in many cases details of components withstanding the overall recording of the piece or event. At what point is the documenting of a work crossing a threshold and entering the realms of ‘image making’? Thus possibly becoming unfathomable and set aside from the original work in question. Is it possible for these, debatably over aestheticise images to bring forth nuances otherwise easily overlooked? How important is this form of aesthetic practice and does it provide a nexus to a greater knowledge; an understanding or acknowledgement of the totality.

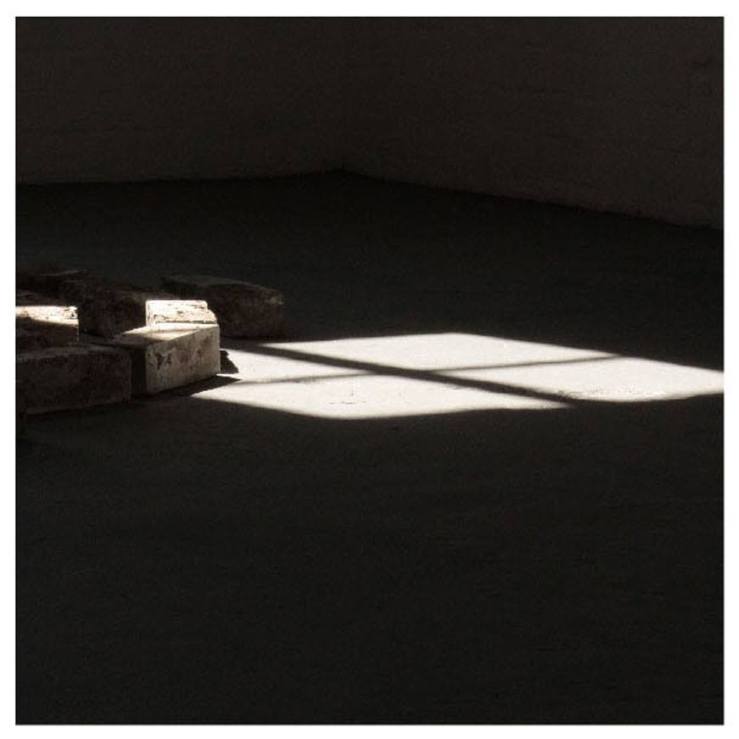

Whether this is an acceptable part of a contemporary fine art practice or not is it over aestheticising, adding a potential layer of theatrical play? Fig.6 . By this I refer to dramatisation during image production processes.

It could be argued that scrutinising works in a two dimensional way is methodology for discovery; a finer observation of materials along with relationships that one hand may seem opaque and without an instant delivery of a narrative. It highlights happenstance alongside elemental situations Fig.2. It might bring about an individual aesthetical pervasiveness together with further responses; further questioning might arise within the analysis and reading of the work. This, I feel at the moment is satisfactory to practice in so far that I see the documentation or image making as a way of seeing, another way into the work and its aesthetic dialogue not compromising the intended meaning or reading of the art work at large. John Berger speaks of the importance of the image and how significant it is to show what we want people to see quite eloquently put, ‘we only see what we look at’ (Berger, 2008, p.8). I am, therefore providing relevant and important information within the images that can inform and engage a reader or viewer of the entirety of the work. I might suggest that this is indeed an activity to direct a viewer to not rely totally on a gestalt viewing; seeing the whole as more than the sum total of its parts, although this is of course equally as essential. The documentary images are to really ‘see’ what it is the viewer is indeed looking at. This statement does however suggest that the images are part of the work installed at any one given time, an arising critical point to digest for both past and for future instalments of all work as this point alone bring questions to be considered.

The image making process within practice strikes a chord with my aesthetical direction and further still, resonates with something private, moreover, instinctive and intuitive; a yearning towards a type of esoteric image making perhaps, nonetheless consequentially seeing aspects of the work in isolation. What can this offer in terms of an aesthetical meaning? Does it change the response to the images documenting or otherwise? Furthermore do they make any sense? These nuances in isolation; do they matter? Are they then at this point redundant and without purpose? An objective response might not be so objective in that there is a vested interest, but at this point I will add that a certain depth of awareness is to be established therefore examining the work as a whole, equipped and inquisitive.

There are certain aspects of image making for this particular purpose that is sought out, for instance;

Content. What am I seeing through the lens that I can’t see as I view the work as a whole?

Context. Am I showing a key aspect of display that is integral to the work or the importance of place?

There are times when out of content and context the image appears from the materials creating its own aesthetic dialogue. This can manifest into metaphoric relationships between the work and self as the author of the image, with a greater understanding of an observation triggering implicit knowledge and an intuitive dialogue.

The documentative images on view in this report were taken in 2016 whilst making works entitled Circular Ruin. Two of the images were taken when the work was in situ at Albus 3 Arts in Northampton 2016, Fig. 5 & 6. These two images were made in order to exemplify not just the work itself but how the work was placed deliberately in order to interact with the light pouring in from a low level window. A strategic placement making the most of the immediate surroundings and the inherent character of the building; an old town brewery since 1919 with the upper storey converted into an art space. I subsequently borrowed some of the buildings atmospherics and this particular spot was going to lend me some strong good quality natural lighting in order for me to make some low key digital images that might add some of that ambient characteristic of the space which I felt suited the essence of the work.

Material enquiry is a key part of practice. Times when the materials themselves require thought the nature of the matter, its uses, and its origins and make up, all become part of and parcel of the work. Its beauty in strength or furthermore, fragility becomes addictive and conative with our own human strength. Author of Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett identifies with a theory concerning the human to that that of the non-human bodies/matter and the active striving for a shared continuity and existence appropriate to materiality configuration. (Bennett, 2010, p.2). Matter is vibrant with inclusions often taken out of quotidian existences and used as a conduit into the work. Hinting towards a life before.

Images often express the contrast of materials in various states; burnt, broken familiar and unfamiliar without name and title. The neutrality tone of cement is surrounding the intentionally charred wood therefore, giving way to the nature of construction, speaking of their creation. Questions may arise from identifying states of matter, once more looking inwards and squaring with our own material state.

On the other hand the image can translate into alterity; a sense of something ‘other’ possibly situated in the realm of liminality between the image and the subconscious. The viewer may experience an unfathomable and unknowable ‘thingness’.

The uninterrupted light fell in the interior framed by a suitably located window bearing a low sill. This informed the space allowing me to plan where the sculpture was to be positioned in order to take full advantage of the changing atmosphere and visual appearance. Throughout daylight hours the contrast and saturation of the light altered mood while highlighting the symmetry and careful placement of the two concentric circles.

As the stones lay static, motionless, and silent, the light brought time and vibrancy. Dust particles or motes pirouetted in the shaft of light above the stones giving a strange air of absence. An otherness was brought into the space; a super trooper examining slowly, intensely stones laying in formation with no beginning and no end whilst their matter gently fell away from their bodies no too unlike a personal and private morphing entropy.

It is evident to me as artist and author of works that this is absolutely necessary and quite a natural process to document in such a way bringing the media of photography into the process; intermediality. What seems like an over aesthetical discourse is in fact a vital part of practice.

A side effect from a process has gained meaning having a role to fulfil within a body of work. Furthermore, a way of seeing the work, how I wish to see it and understand it is captured in this form of documentation. As for consideration for a viewer it is not for me to second guess any individuals response nor shall I take it for granted that any other viewer seeks the same narrative as the makers. I have presented a door in which one decides on the level of engagement. What can be found is as personal to the audience as it is to the maker.

Bibliography:

Beardsley, J. [1998]. Earthworks and Beyond. 3rd Ed Cross River Press, Ltd. USA.

Bennett, J. [2010] Vibrant Matter, a political ecology of things. Duke University Press UK

Berger, J. [1984] And our faces, my heart, brief as photos. Pantheon Books USA

Berger, J. [2008] Ways of Seeing. Penguin Publishers UK

Cage, J. [1987] Silence. Lectures and Writings. Marion Boyars publishers’ ltd London Uk

Cage, J. [1992] The Roaring Silence: A Life. Bloomsbury publishers London UK

Dean, RT. Smith, H. [2012]. Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts.

Dillon, B. [2014]. Ruin Lust. Harry N. Abrams,

Dillon, B. [2011]. Ruins (Documents of Contemporary Art). Whitechapel Art Gallery, London. Edinburgh University Press UK.

Kaye, N. [2000]. Site Specific Art. Performance, Place, and Documentation. Routledge Oxen UK.

Long, R. [ND]. Walking the Line, Paul Moorhouse and Denise Hooker. Thames and Hudson London UK.

Long, R. [2009]. Selected Statements and Interviews. Haunch of Venison UK.

Author: Sharon Read

Images & Content © 2015 Sharon Read